The Snowdrop

Lost in the Arctic

Part I.

The Smallest Whaler

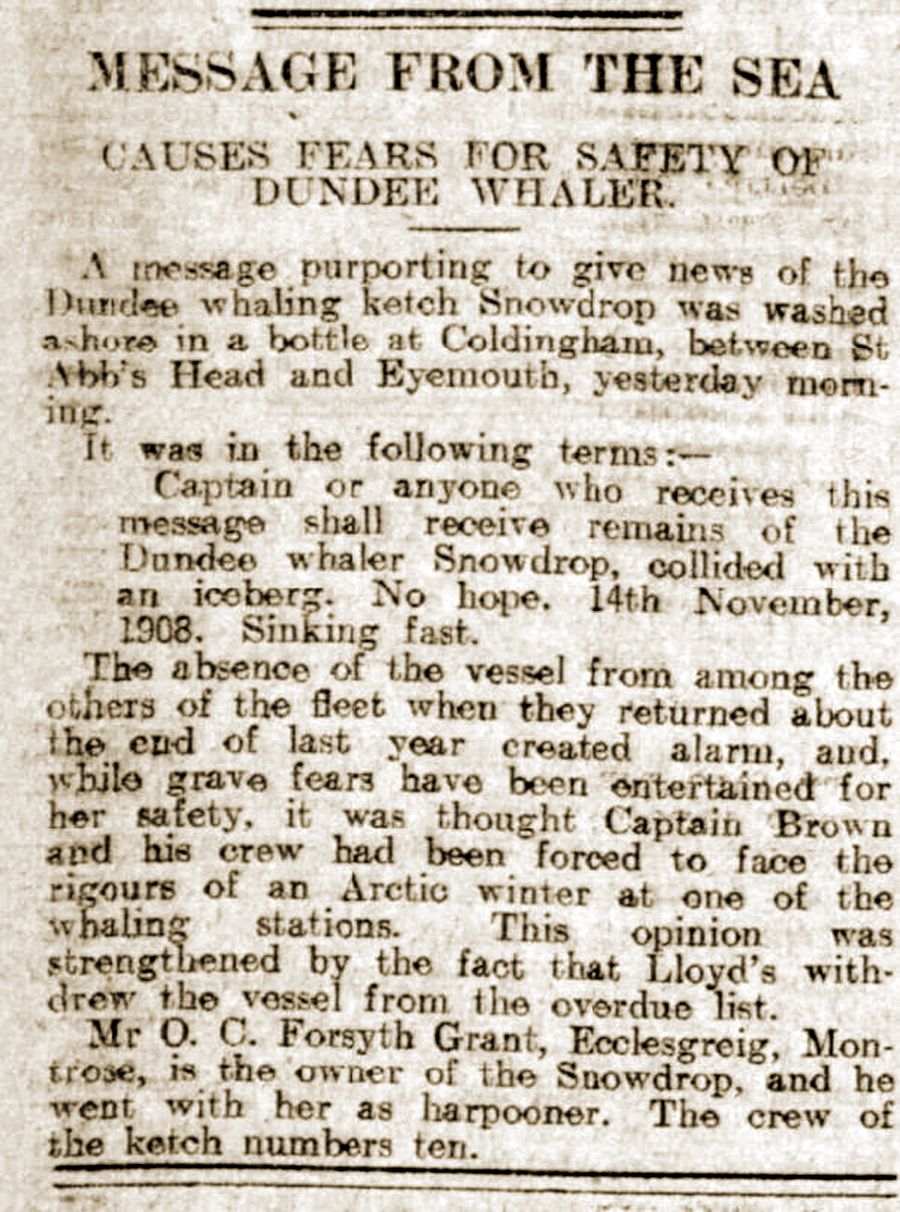

“Captain or anyone who receives this message shall receive remains of the Dundee whaler Snowdrop, collided with an iceberg. No hope. 14th November, 1908. Sinking fast.”

The message in a bottle washed ashore on a rocky beach at Coldingham Bay, Scotland, on the morning of March 11, 1909. For anxious relatives and friends, the hastily-scrawled note seemed to confirm their fears that the two-masted sailboat and its ten crew members were lost at sea.

The Snowdrop had departed from Dundee almost a year earlier as part of a small whaling fleet bound for the Arctic waters of the Davis Strait between Greenland and Canada. It was last seen there in the summer of 1908 and reported as “All well.” But when the fleet returned to Dundee with its catch of fifteen whales that November, the Snowdrop was missing, and its fate unknown.

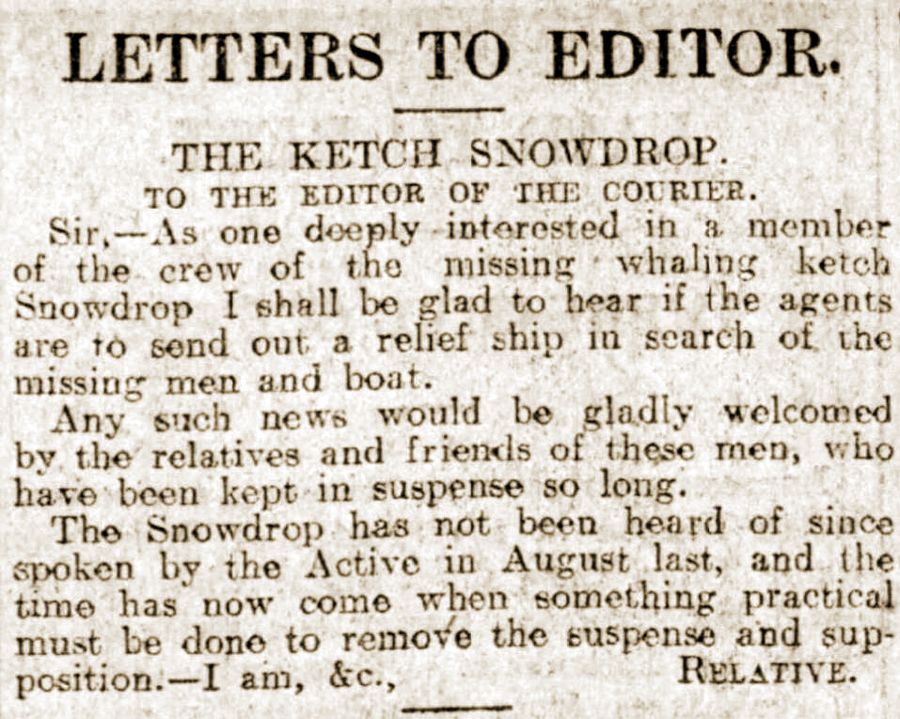

For several weeks, the Dundee whaling community awaited the Snowdrop’s return, expecting that it had been delayed by ice. But by the beginning of 1909, they began to call for shipping agents to send a relief ship in search of the missing boat and crew.

“Any such news would be gladly welcomed by the relatives and friends of these men,” wrote one family member in a letter to the Dundee Courier. “The time has now come when something practical must be done to remove the suspense and supposition.”

Far across the North Atlantic, on a frozen peninsula in the Arctic Archipelago, the men of the Snowdrop were still alive. But they had lost their ship and supplies and were struggling against plummeting temperatures with inadequate food and shelter. To survive, they would need to rely on the skills and generosity of native Inuit families, and the determination and bravery of a young seaman who would set off on an epic journey to escape the Arctic and find help.

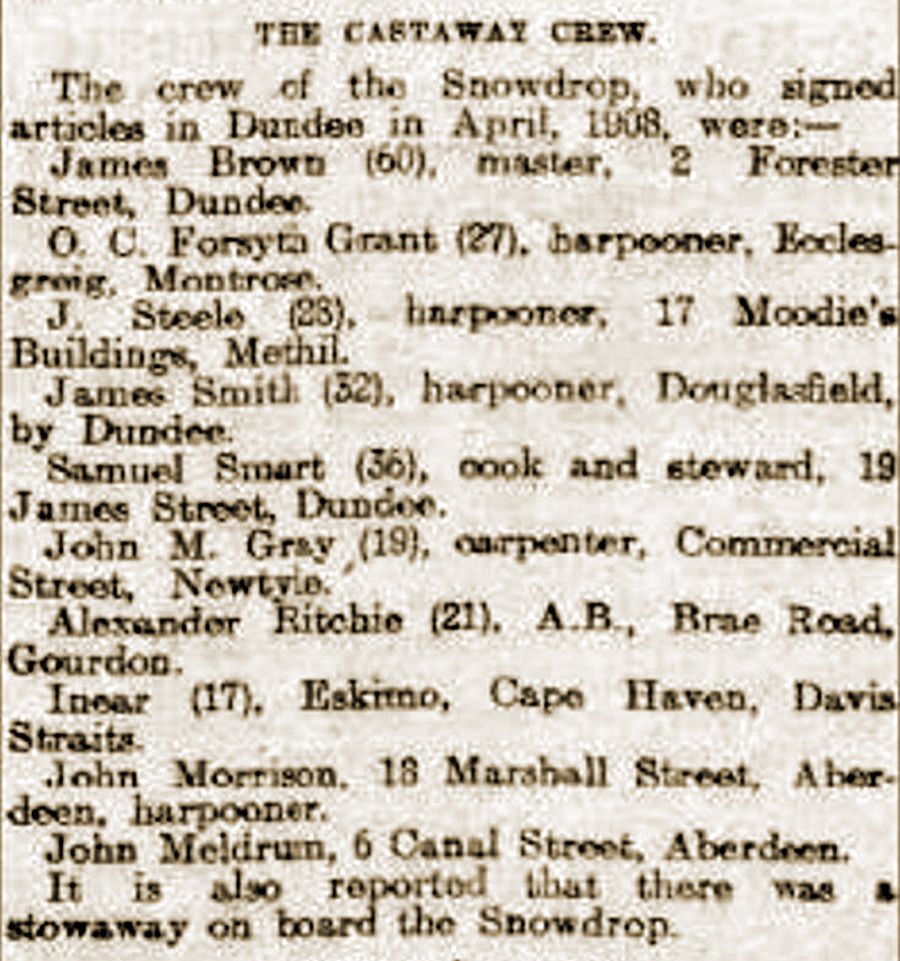

Alex Ritchie was twenty-one when he left Dundee Harbour aboard the Snowdrop, its sails rippling in the North Sea breeze. It was about midday on Thursday, April 23, 1908, and a crowd waved and cheered from the quay. “The weather was good,” Ritchie later recalled, “but all our crew were drunk—from the captain to the cook. Being a total abstainer, I had to take the wheel, and there I had to remain until some of the crew got sober enough to stand.”

Ritchie was the son of a fishing boat captain from Gourdon, a few miles up the east coast of Scotland. Despite his young age, he was already a well-acquainted able seaman (AB), relied upon to serve as helmsman and lookout. He observed a longstanding seafaring tradition by wearing a sailor’s earring. Ritchie was deeply religious and carried a Bible in a handmade watertight case. This was his third voyage to the Arctic with the Snowdrop. It would be his last.

The ship’s captain was sixty-year-old James Brown, an experienced skipper with a tough reputation who had first gone to sea at fifteen. Brown had whaled in the Arctic for many years and was fluent in the languages of the native Inuit. Among the otherwise all-Scottish crew was a seventeen-year-old Inuit named Inear, the son of a native leader, who was returning home after traveling to Scotland with the Snowdrop in the previous year. (Inear would be able to teach his community a new skill he had learned: knitting.)

The Snowdrop was owned by Osbert Clare (OC) Forsyth-Grant, the twenty-seven-year-old son of a Scottish Laird who resided at a gothic pile near Montrose named Ecclesgreig Castle. He was obsessed with Arctic adventure. Although his military-minded father disapproved of OC’s intention to become a whaler, he did finance the purchase of the Snowdrop. The wooden ship had been built in Scarborough, England, in 1886, twenty-two years before its fateful final journey to the Arctic.

Known locally as “the smallest whaler,” the Snowdrop was a type of sailboat known as a ketch, rigged with a mainmast and a missin. At about fifty feet long, it was unusually small for a whaling ship. But it had a secret weapon—a forty-horsepower engine, a rarity in vessels of its size. It was fitted out with large tanks for blubber and whalebone, the voyage’s chief prizes. Dundee, in particular, relied on oil rendered from blubber for its jute factories.

On its previous voyage, the Snowdrop caught a whale that was bigger than the ship. After spotting the whale, the crew launched their boats and got within close range. Forsyth-Grant fired a harpoon that “got fast.” The stricken whale plunged away, reeling out the boats’ lines. But “the fish was not a stayer.” It came to the surface and was killed by a bomb lance thrust into its vital organs. The crew pulled the whale’s body alongside the Snowdrop, then—without any possibility of winching the huge animal aboard—improvised their grisly efforts to strip it of blubber and remove its bones. On this new voyage in 1908, the Snowdrop expected to catch one or two good-sized whales and perhaps several hundred walrus and seals.

The transatlantic voyage from Dundee to the Davis Strait was one of more than three thousand miles. But the Snowdrop had barely traveled fifty when it ran into a fearsome gale and was forced to dock at Aberdeen. Two crewmembers—already seasick—went ashore and never returned. The deserters were replaced by two Aberdeen men, John Morrison and John Meldrum, and the crew was further bolstered by the discovery of a young stowaway named John Robertson. He was signed on for the journey at a wage of one shilling a day. There were now eleven individuals aboard the Snowdrop—ten Scotsmen (including four Johns and three Jameses) plus the Inuit teenager Inear.

Once the weather cleared up, the crew sailed around the head of Scotland and crossed the Atlantic. Thirteen days after leaving Aberdeen, the Snowdrop was in the frigid waters off the west coast of Greenland. “Not bad sailing for a small ship,” remarked Alex Ritchie in his oral account, which was transcribed by a family member.

The Snowdrop photographed in the Arctic

The Snowdrop photographed in the Arctic

The Snowdrop photographed in the Arctic

The Snowdrop photographed in the Arctic

The Snowdrop photographed in the Arctic

The Snowdrop photographed in the Arctic

When they arrived, the average temperature was around minus seven degrees Celsius (nineteen degrees Fahrenheit), and the ocean was filled with ice floes and bergs. The crew spent several weeks searching for whales and walrus, edging north into the Arctic Circle as far as the gradually rising temperature and melting ice allowed. Then, when summer approached and the floes cracked and opened, they headed across to Cape Haven, a small settlement known to the Inuit as Singaijaq on an eastern peninsula of Baffin Island, almost two hundred miles north of the Canadian mainland.

OC Forsyth-Grant had previously established a rudimentary trading station at Cape Haven, with wooden huts and a storehouse. Most importantly, he had established a friendship with the native people, who hunted and traded with him. They called him Mitsiga. During his time at Cape Haven, he lived with the community’s chief trader, Gotilliaktuk, known to the whalers as Mr Mate. Inear, the young Inuit who had traveled with Forsyth-Grant to Scotland, was the son of Gotilliaktuk and his wife Nangiaruk.

The Snowdrop put ashore all of its spare stores—around seven tons worth—and took aboard the entire settlement’s population. According to Ritchie, this amounted to sixty-five men, women, and children, plus their dogs. This was the custom of the Scottish whalers, who would sail with small crews and rely on the skills of local communities at their destinations. And it was the custom of the Inuit to take their entire families with them.

“They were to hunt for us; walrus, seals, bears, and foxes,” explained Ritchie. “There were only ten of us white men, so they helped us a lot. The women did all the rowing in the boats, and the men the shooting. Then the Eskimo would take a day or two deer hunting—they are very good shots—to get deer skins for their beds and winter clothing.” Ritchie called the natives Eskimo, a term often used by outsiders, but they referred to themselves as Inuit, meaning “the people.”

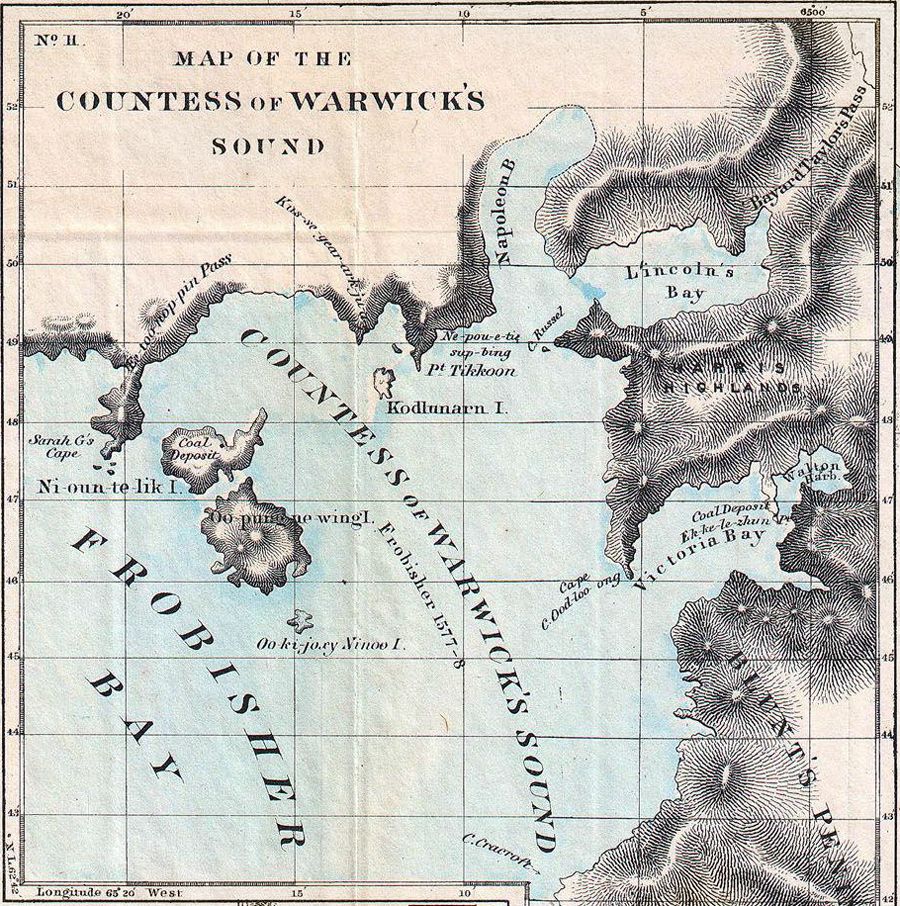

After several weeks of hunting, the Snowdrop’s storage tanks were full. According to Ritchie, although they had not caught a whale, they had six hundred and fifty walrus and six hundred seals, plus many polar bears and Arctic foxes. The plan was to take the Inuit community back to Cape Haven, then return with their catch to Dundee. The Snowdrop came to anchor in a Frobisher Bay inlet known as the Countess of Warwick Sound. It was September 18. The ship had been at sea for five months. Then came the storm.

Part II.

The Wreck

We were making everything ready for our voyage home,” said Ritchie, “when the wind started to blow very heavy from the East.” The anchor began to drag as the rising gale drove the ship through broken ice floes toward the rocky shore. Tumbling rushes of frosty waves crashed over the bow, and Captain Brown sent the women and children down into the hold for fear they might be swept away. “We knew that it was going to be a bad business for us all,” said Ritchie, “as it seemed we could do nothing to help ourselves.”

Brown ordered the engine powered at full speed to pull the ship away from the shore. But the strain on the anchor had broken its windlass, and it couldn’t be raised. The ship was going nowhere. Ritchie went down to the chain locker with a hacksaw to try to cut the anchor cable, but the saw blades shattered. Now the experienced Captain Brown said it was “blowing a hurricane with blinding snow.” The crew tried to consolidate the ship’s position by lowering another anchor. “Just as we had everything complete,” said Ritchie, “both the anchors gave way and we drove on the rocks.”

At the first strike, the ship began to break apart. In the fierce snowstorm, lashed with breakers and surrounded by crags of rock and ice, the crew and the Inuit would need to abandon ship and reach the beachy shoreline—or perish. The men attempted to lower the ship’s dinghy but the conditions made it impossible. The only path to land was over the rocks and cracked ice floes, using them as slippery stepping stones.

Captain Brown yelled to his crew over the noise of the wind and the waves: “Is there any of you think that you could manage to go ashore with a rope?”

“Nobody spoke as it seemed so hopeless,” recalled Ritchie. “Then I said I would have a try.”

“Alright,” yelled the Captain. “If you do get ashore, you’ll have to come back.”

“I thought that was a rather tall order,” recalled Ritchie. “I thought if I got ashore, it would be a good enough day’s work.”

After a precarious struggle, his feet and hands slip-sliding in the wretched conditions, Ritchie made it over the side of the ship and across the rocks and ice onto the beach with a rope. He secured the end of the rope to a large boulder. Then he climbed back to the Snowdrop, heaving himself hand-over-hand along the rope.

The crew then used the rope to haul the Inuit off the sinking ship, before climbing clear themselves. “We got everybody, old and young, ashore and did not lose nor hurt anyone,” said Ritchie. Captain Brown’s log recorded that there were forty-one Inuit onboard at the time of the wreck, including eleven children. All had survived. But the crew had lost almost all of their possessions—their food, supplies, and catch. The only belongings Ritchie saved were his Bible, hurriedly rescued from his bunk, and his socks and mittens, which were sewn inside his jacket—a common whaler’s custom.

The men huddled on the shore and watched the Snowdrop break apart. The hull shattered and the masts collapsed. The ship’s four whaleboats were washed away. “We were all thankful for our escape,” said Ritchie, “but we had nowhere to go for shelter.” Fortunately, after the hull burst, some supplies began to wash ashore. The Inuit rigged up a tent using the ship’s spare mainsail and made fires with pieces of blubber. There was very little food, but the Inuit helped the crew dry their clothes and get warm. “We got them ashore,” said Ritchie, “but they kept us alive.”

The Scots and the Inuit sheltered in their makeshift tent for four days. After the storm subsided, they spotted one of the whaleboats in the water near the wrecked ship. The men patched up their damaged dinghy with animal skins and paddled out to retrieve it. Then Ritchie and three of his crewmates, plus an Inuit named Nuna and his two daughters, set out in the whaleboat for the top of Frobisher Bay. According to the Inuit, the land there was narrow, and they could travel across to the Hudson Strait, between Baffin Island and the Canadian mainland, where a rescue ship might pass.

It took seven days to reach the top of Frobisher Bay. The party hauled up their boat and erected a tent for the night. Then a blizzard struck. By the morning, the snow had buried the tent and blanketed the icy ground, obscuring deadly cracks and crevasses. The Inuit said it was too dangerous to continue. “So that finished that,” said Ritchie. The party traveled back to the wreck site. When they got back, the ship had completely broken up.

“We then had another try,” said Ritchie. This time, the entire Snowdrop crew set off in the whaleboat. But, after being stuck on an island in Frobisher Bay for seven days in a howling gale, they returned to the wreck site. When they got back, the Inuit had left for Cape Haven. The crew followed them, trekking across ice and snowfields and over hills and frozen lakes. It took them six days to reach the Inuit settlement.

The Snowdrop had put more than seven tons of stores ashore at Cape Haven. But there was not enough food for what now seemed likely to be an entire winter trapped in the Arctic. OC Forsyth-Grant, as the owner of the stores, took control of the rationing. Ritchie said that Forsyth-Grant hardly gave him anything. As supplies dwindled, each man was limited to one ship’s biscuit per day. That was not enough to live on, and they depended on the Inuit for extra food. And there was not enough room for the ten-man crew in the station’s huts, so several of them depended on the Inuit for shelter.

Ritchie lived with the Inuit in a sealskin tent (tupiq) and went hunting with them. He noted how they hunted seals using trained dogs to find breathing holes in the ice. “The seal has got several holes, and you may have to stand at one of these for hours,” he said. “Sometimes an Eskimo has stood as long as three days before the seal came to the hole where he was standing ready to harpoon it.” When the Inuit caught a seal, they would share it with their community.

Dundee Courier, Jan 30, 1909

Dundee Courier, Jan 30, 1909

Dundee Courier, Mar 11, 1909

Dundee Courier, Mar 11, 1909

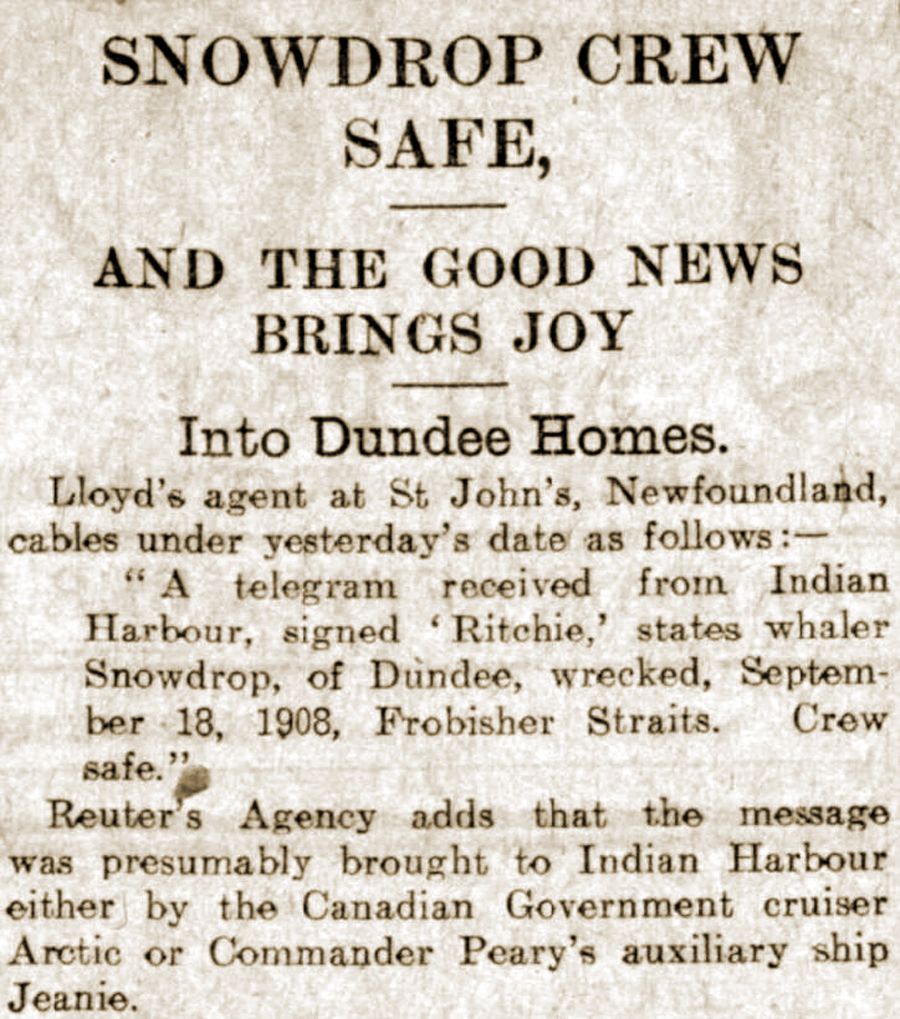

Dundee Courier, Sept 27, 1909

Dundee Courier, Sept 27, 1909

One day, ignoring warnings from the Inuit, Ritchie went hunting alone. He traveled a long distance across the ice floes looking for seal holes and found none. So he headed back, walking quickly to stay warm and beat the sunset. He didn’t notice a crack in the ice. “And all of a sudden, I just dropped right down into darkness, utter darkness,” he said. “I knew that I was in water. And I thought, now, this is the last.”

The ice floe was about nine feet deep and its surface was about three feet above water level. Ritchie needed to launch himself out of the water and grab the edge of the floe. In the freezing conditions, he only had one chance: “I knew if I did not get out at the first attempt while I was strong, I would not get out.”

Making his leap, Ritchie caught the edge of the ice with the fingertips of his right hand, then grasped on with his left hand. He gradually pulled himself up, getting one elbow onto the ice and then the other, before falling forward onto the floe, utterly exhausted. But—aware that delay meant death—he dragged himself to his feet, soaked and freezing, and staggered back to Cape Haven.

“When the Eskimos saw me, they were amazed,” he said. “They took off my frozen clothes and rubbed all my body to get warmth and circulation. I never went away alone again, I always paid attention to what they told me. After that day, they named me Kivvy Actow. It means ‘man that was nearly drowned.’”

As winter approached and the weather grew colder, the Inuit abandoned their tents and built snow houses or iglu, which offered better protection from the elements. Ritchie lived with a man named Goodilack and his wife Cumni. He came to enjoy their company and customs, particularly their feasts, when an Inuit who caught a seal would invite everyone to come and eat, sing, and dance. But seals became scarce, and the community resorted to eating blubber and seaweed. The Inuit decided to move on to hunt for food.

On December 16, Ritchie and four of his crewmates—John Morrison, Jimmy Steele, James Smith, and John Robertson—left Cape Haven with their Inuit families. The Inuit would look for food and skins, and would try to get Ritchie and the others to the Hudson Strait with the hope of finding a ship. They endured terrible conditions and spent four days over the New Year hunkered down in a small snow house on the ice as a blizzard raged from the north. “The Eskimo do not like north winds,” said Ritchie. “They call it vagnar. Nothing can live in the open with a north wind.”

At the beginning of February, Ritchie’s crewmates decided they could go no further, and they would return to Cape Haven with their Inuit families. One of the men, John Morrison, was suffering terribly from frostbite, which was spreading from a blackened big toe up his foot. Ritchie asked the Inuit what they could do. They replied that they would take it off. Without anesthesia, their method was to knock the patient out with a sandbag to the head, then attack the frost-bitten limb with an ice saw. Morrison initially refused their assistance, and gangrene caused by the frostbite began to spread up both of his legs.

Ritchie pressed on with the remaining Inuit in a final effort to reach the Hudson Strait. During the journey, the party crossed an ice cap known as Grinnell Glacier, which was almost three thousand feet high at its tallest point. Ritchie began to suffer from exhaustion and struggled to keep up. The Inuit told him to hold on to the lashings at the back of their sled, but he was too tired and kept letting go. Daylight was fading, and the fractured ice was too dangerous to negotiate at night, so they had to push on. Ritchie fell behind, and the Inuit vanished. Hours passed, darkness fell, and swirling snow obliterated the sled tracks. He was hopelessly lost.

“I lay down thinking it was all over,” he said. “I thought, what a struggle I have had, and now I was going to be frozen to death.”

“I lay and was very cold and had given up hope, when I thought I heard voices.”

Two Inuit had returned, carrying their dogs and sled over crevasses in the darkness. They had expected to find him dead.

After recovering in their snow house, Ritchie and the Inuit made the long and difficult climb up the desolate glacier. Eventually, they reached the top. “It was a grand sight,” said Ritchie. “In the clear frosty air we could see for miles and miles all the frozen land and the sea lying away on the horizon.”

After four days on the glacier, they reached an Inuit village at Saddleback Island. Unfortunately, the villagers had no food. Ritchie said he was the hungriest he had been on his entire journey. They moved on toward Lake Harbour or Kimmirut at the top of the Hudson Strait, around a hundred miles north, and arrived on April 1, four and a half months after they had left Cape Haven. But any relief was short-lived. Ritchie was very ill.

“My face all seemed to be queer somehow, and I asked the people if there was anything wrong, and they said yes.” It seems likely he was suffering from scurvy due to a prolonged lack of vitamin C. He passed out and fell into a coma. The Inuit counted their time by sleeps. According to them, Ritchie was unconscious for twenty-one sleeps.

Part III.

The Rescue

Ritchie awoke in a snow house that was beginning to melt—a sure sign that spring was arriving. Outside, he could hear rivers running—“the most beautiful sound I had ever heard.” Food was plentiful because flocks of eider ducks had arrived and were nesting all over the settlement. He was too weak to walk, but the Inuit made a hole in the snow house, pushed a sled inside, and dragged him to a tent. He began to recover, but couldn’t rest for long. The Inuit were heading back to Saddleback Island, where, they said, the Dundee whaler Active could be found.

Luckily for Ritchie, he would not have to trek all the way back to the island. When they reached the edge of the Grinnell Glacier, the party spotted the Active anchored off the coast. It was stuck in pack ice and waiting for the melt. Ritchie and the Inuit crossed the ice and went aboard, although Ritchie was almost too weak to climb the side ladder.

Onboard, the crew welcomed the arrivals with handshakes. Ritchie was amazed to see three men he had sailed with on a previous voyage. Such was his weatherbeaten and emaciated condition, none of them recognized him. The crew gave Ritchie tea and a bun, then weighed him using a stilyard balance. He weighed just seven stone (ninety-eight pounds) in his clothes and boots.

The Active had to continue its hunt when the ice opened up, but would take Ritchie home on its return voyage. So, he went ashore to wait at a settlement used by mica mineral miners. Ritchie stayed with the Inuit, and made food for the miners when they returned from the mine every Saturday. He knew it would be a long wait for the Active. But, after several weeks, another boat arrived. This was the Lorna Doone. Ten months and perhaps five hundred miles after leaving Cape Haven, it would be his rescue vessel.

After saying bittersweet goodbyes to his Inuit friends, Ritchie left Baffin Island on the Lorna Doone for St Anthony, Newfoundland, almost a thousand miles south. Along the way, Ritchie was able to send a telegram with a Lloyd’s shipping agent: “Whaler Snowdrop, of Dundee, wrecked, September 18, 1908, Frobisher Straits. Crew safe.—Ritchie.”

Then he traveled on a steamship named Prospero to St John’s, arriving at Canada’s easternmost tip on September 18, 1909—exactly one year after the wreck of the Snowdrop—with only the North Atlantic separating him from home.

Dundee Courier, Sept 17, 1909

Dundee Courier, Sept 17, 1909

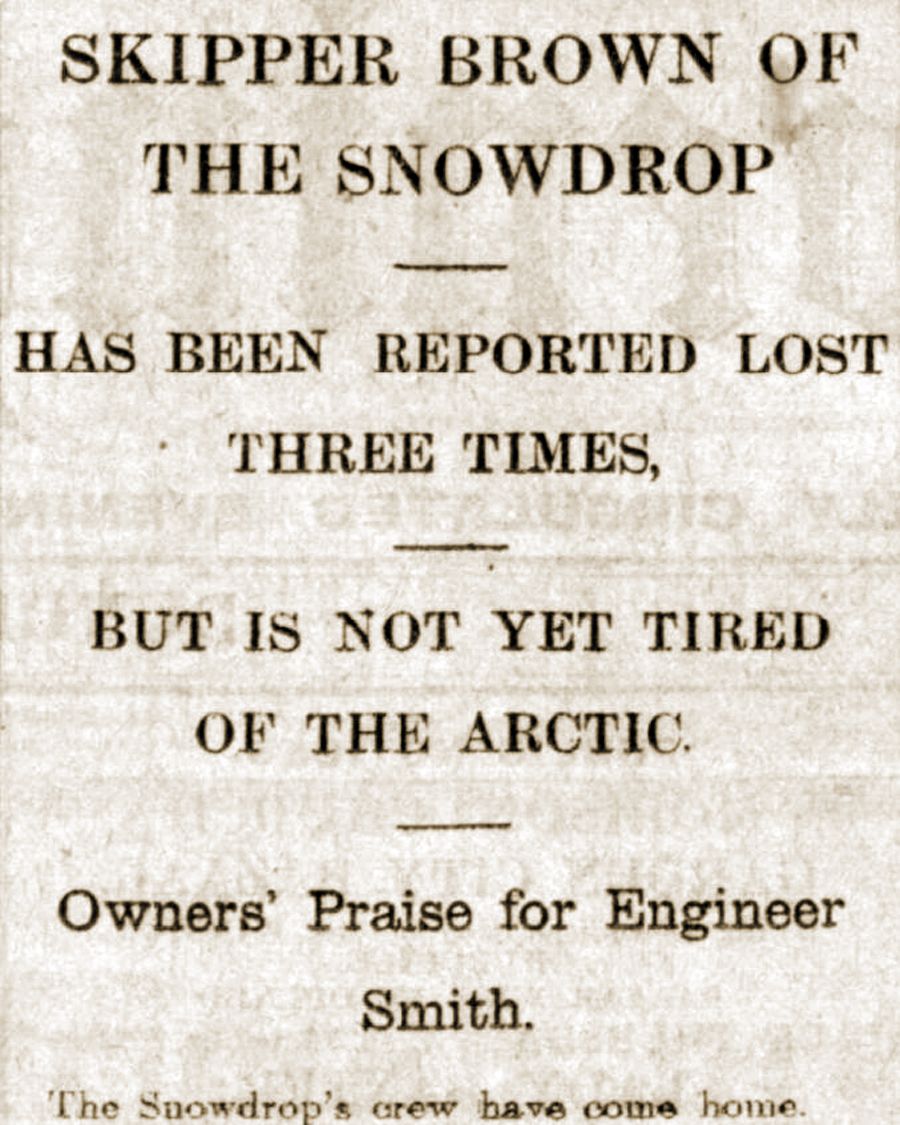

Dundee Courier, Oct 18, 1909

Dundee Courier, Oct 18, 1909

Dundee Courier, Oct 18, 1909

Dundee Courier, Oct 18, 1909

Ritchie had always been mindful that he needed to arrange a rescue for the remainder of the Snowdrop crew, but the rescue was already underway. A few days later, a ship arrived in St John’s carrying the entire crew—except one. John Morrison, riddled with frostbite and gangrene, had allowed the Inuit to amputate parts of both his feet—the left foot above the toe joints, and the right at the forefoot and heel—and had remained with them to recover. Captain Brown, OC Forsyth-Grant, and the others had been rescued by an Arctic exploration vessel, the Jeanie.

The return of the Jeanie to North America was much anticipated because the world was waiting to hear which of two competing explorers had been first to reach the North Pole, Frederick Cook or Robert Peary. The crew of the Snowdrop unwittingly became involved in this much-reported story. The Jeanie was expected to be carrying Cook’s navigation records as proof of his claim. But the records had been lost. Neither Cook nor Peary was able to prove his claim—and waiting newspaper reporters were instead presented with the long-lost crew of a wrecked Scottish whaler.

The Snowdrop crew sailed back to Scotland on the steam liner Siberian and arrived in Dundee on October 16, 1909, almost eighteen months after they had departed.

Captain Brown was delighted to be home—his only woe being the loss of his spectacles. “Man, I left them behind,” he told newspaper reporters, adding that he was not tired of the Arctic. “I am going out next year if I get the chance.” Jimmy Steele, the ship’s mate, said he, too, would return to the Arctic in the following year.

OC Forsyth-Grant told reporters he was keen to know who had performed the “rascally trick” of sending the message in a bottle—now exposed as a cruel hoax. He had no idea that he and his companions were being mourned as dead. Although the Snowdrop had been wrecked, the crew had never given up hope, he said.

On the enduring question regarding the whereabouts of John Morrison, Forsyth-Grant said he had personally seen him in July and, although he was too ill to be moved, he was recovering. “We certainly gave him plenty of stuff to eat,” said Forsyth-Grant, “and he ought to be alright.”

As for Alex Ritchie, a Dundee reporter visited him in Gourdon and found him to be very well, and very modest. “It was with difficulty that he was made to speak of the trying winter in the Arctic regions,” wrote the reporter. Ritchie did say that reports stating he had single-handedly gone for help were false. He had been in the company of the Inuit, he said, and could not have survived without them.

Dundee Courier, July 24, 1909

Dundee Courier, July 24, 1909

Dundee Courier, Oct 5, 1910

Dundee Courier, Oct 5, 1910

Dundee Courier, Oct 17, 1912

Dundee Courier, Oct 17, 1912

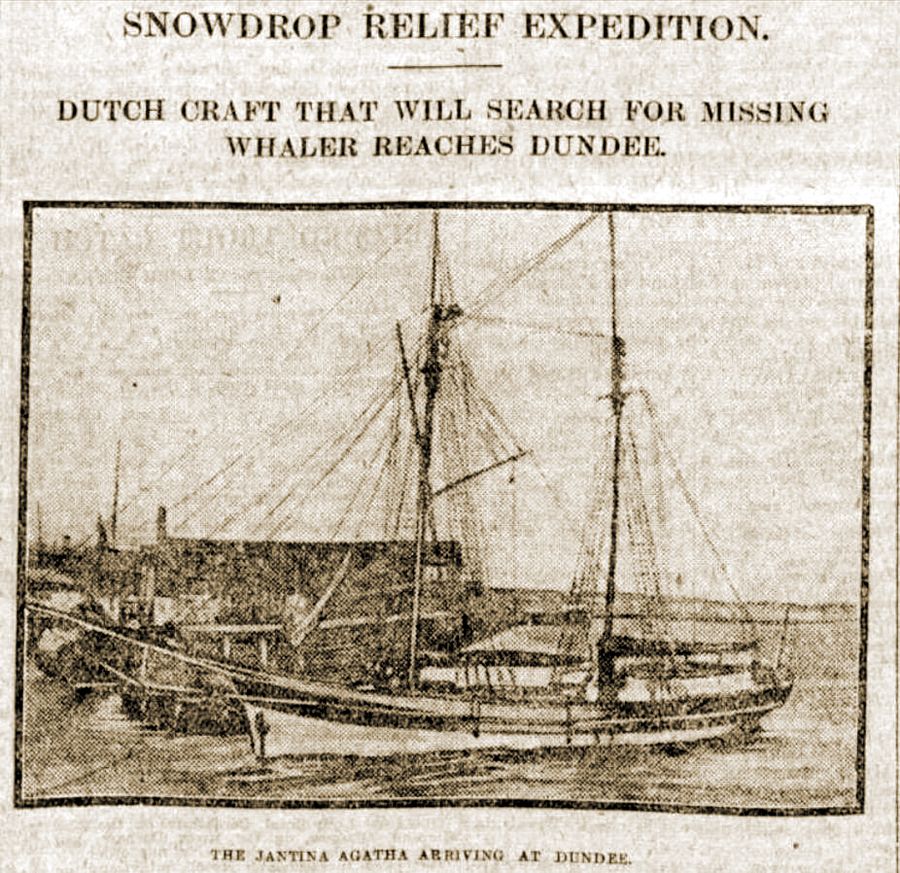

The tribulations of the Snowdrop story did not end there. Under pressure from friends and relatives, Dundee shipping agents had sent a Dutch schooner, the Jantina Agatha, to search for the missing whaler. The Jantina, skippered by Captain WC Dykstra, left Dundee in July 1909 carrying supplies, letters for the Snowdrop crew, and a missionary, the Reverend Edgar Greenshield. It never returned. “She has disappeared so completely,” said one newspaper, “that the gravest fears are entertained as to her probable fate.”

Another ship, a whaler from Ipswich named the Paradox, had also been searching for the Snowdrop crew and was within twenty miles of Cape Haven when it was caught in a gale and badly holed. The crew fought to stay afloat for a week, before being rescued by a passing steamer. Another newspaper commented: “Perhaps never has such a sequence of shipwrecks and adventure been wrung out of the Arctic in all its long history of death and devastation to whalers.”

In September 1910, the mystery of the missing Jantina Agatha was solved when the schooner Thomas arrived in Dundee carrying Captain Dykstra and several of his crew. The Jantina had struck an iceberg and sunk. The crew escaped in small boats and rowed for forty-five miles through icy waters to reach a trading station at Blacklead Island, where they endured almost a year of near starvation before being rescued.

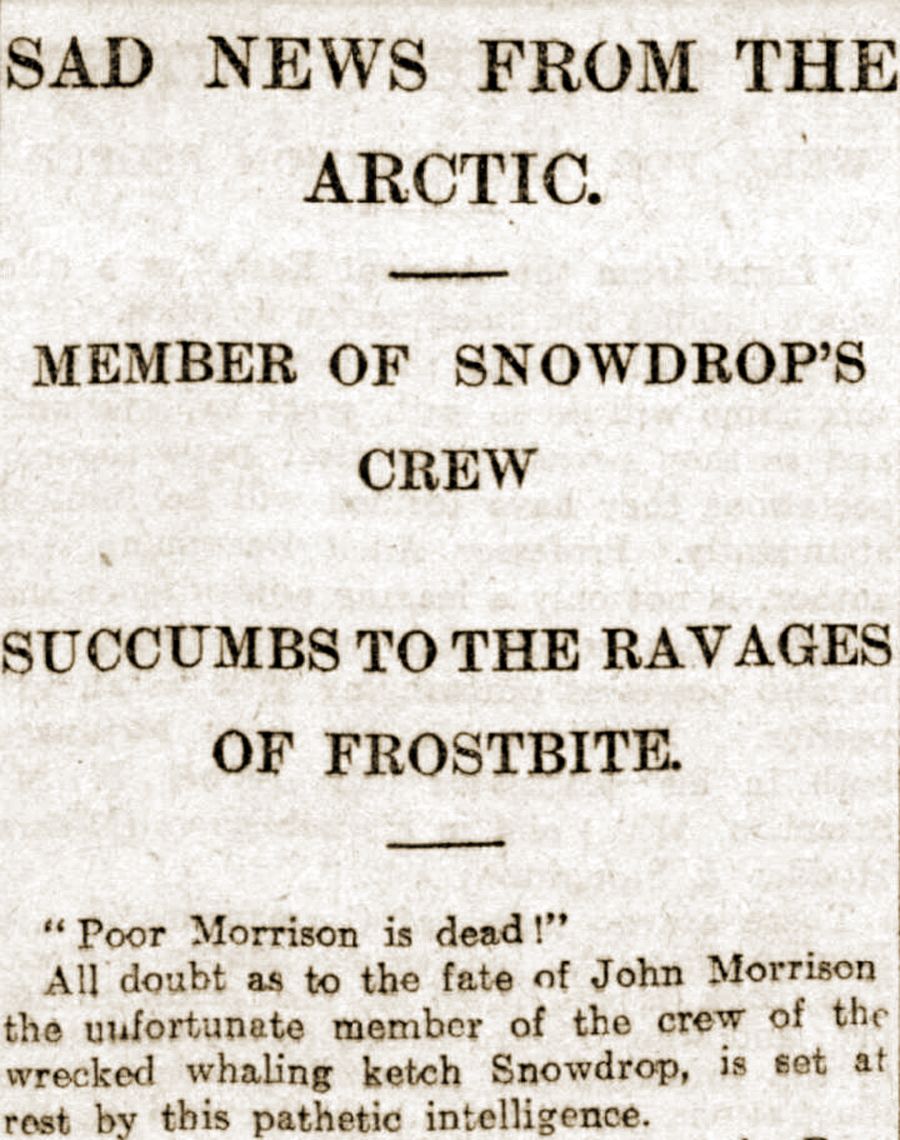

Among those who returned to Dundee on the Thomas was the Reverend Greenshield. And he brought news of the fate of John Morrison. Greenshield said he had heard from his Inuit friends that, after Morrison had been left in their care in the previous year, they had cared for him as well as they could, before “mortification set in.” They attempted a further amputation, but he never recovered. The Dundee Courier reported the tragedy with the exclamation: “Poor Morrison is Dead!”

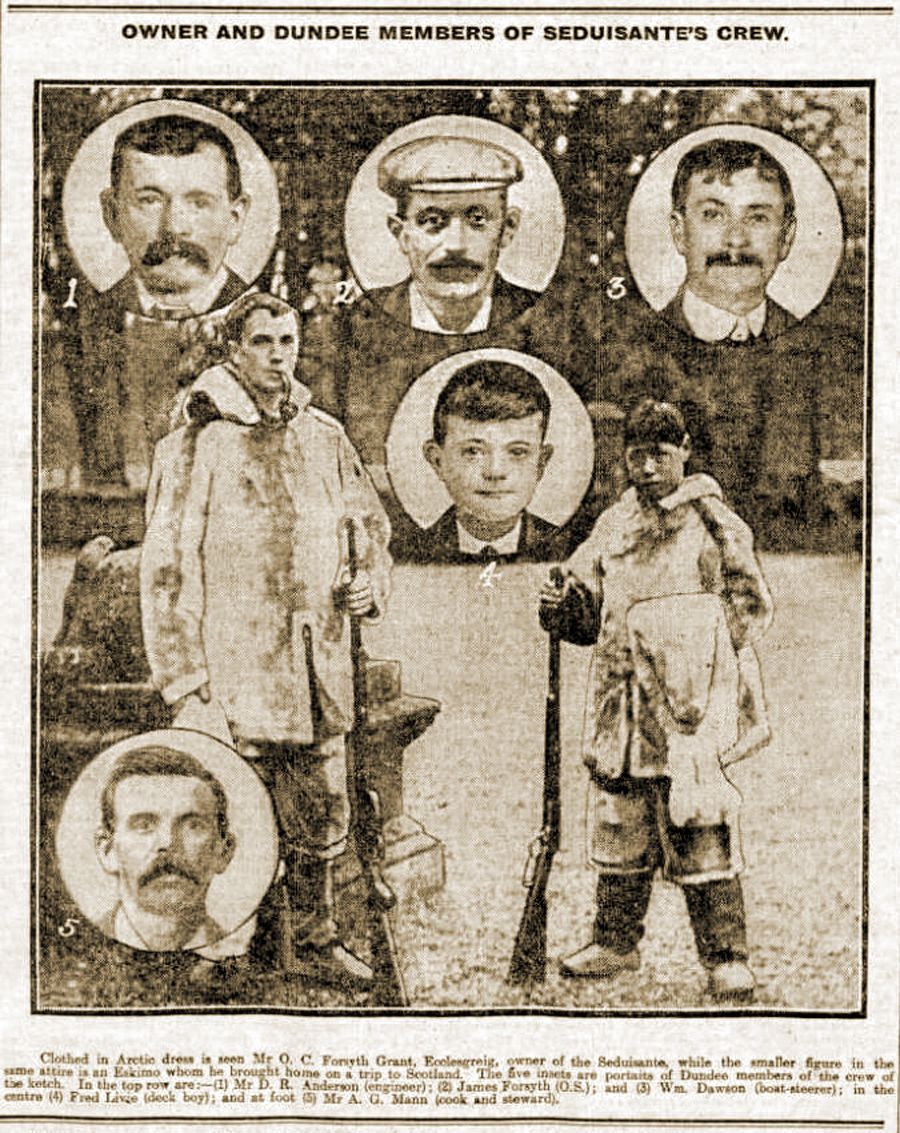

Several of the Snowdrop’s crew remained unaware of Morrison’s fate because they were already back in the Arctic. OC Forsyth-Grant had purchased a new vessel, the French schooner Seduisante, and sailed back to Cape Haven with Captain Brown in April 1910, apparently to search for Morrison and retrieve the Snowdrop’s lost catch. It was another nightmarish journey—a hurricane ripped the sails to shreds, and two crewmen died. “I have sailed the seas for fifty years, but I have never experienced such a voyage as this,” said Brown. “This trip has taken ten years off my life.”

In the following year, Brown declined to sail with the Seduisante to the Arctic. But Forsyth-Grant—now thirty-one years old—went back, along with Snowdrop mate Jimmy Steele, and new captain JR Connon. The Seduisante was wrecked in a gale at the entrance to the Hudson Strait on September 24, 1911. Forsyth-Grant, Steele, and the others all perished. Only two bodies were found—those of Captain Connon and engineer DR Anderson, who had experienced a strange premonition before the voyage and uncharacteristically told his wife, “I don’t want to go, for I will not return.”

Alex Ritchie photographed on a Gourdon fishing vessel

Alex Ritchie photographed on a Gourdon fishing vessel

Alex Ritchie never went back to the Arctic. He worked as a fisherman in Gourdon, and took a stake with his father and brothers in a fishing vessel named the Bella. During the war, while Ritchie was away serving as a naval officer, the Bella was captured by a German U-boat and the crew was held in a prisoner-of-war camp. After the war, Ritchie went back in with his family on a boat called the Happy Return.

In the 1950s, Ritchie gave an account of his Arctic adventure to BBC radio and recalled leaving his Inuit friends on his departure from Baffin Island. “Well, when we left, every one of the Eskimo came down to the beach to say goodbye,” he said. “And the word they said for goodbye was tavvauvutit. When they welcome you they say chimo, and when they say goodbye, tavvauvutit. So I just had to say tavvauvutit, and that was it.”

“I’ve never forgot these people, all my life. I've always wished that I could have been able to go back and repay them, you see. But it was a thing that was impossible.” ◆

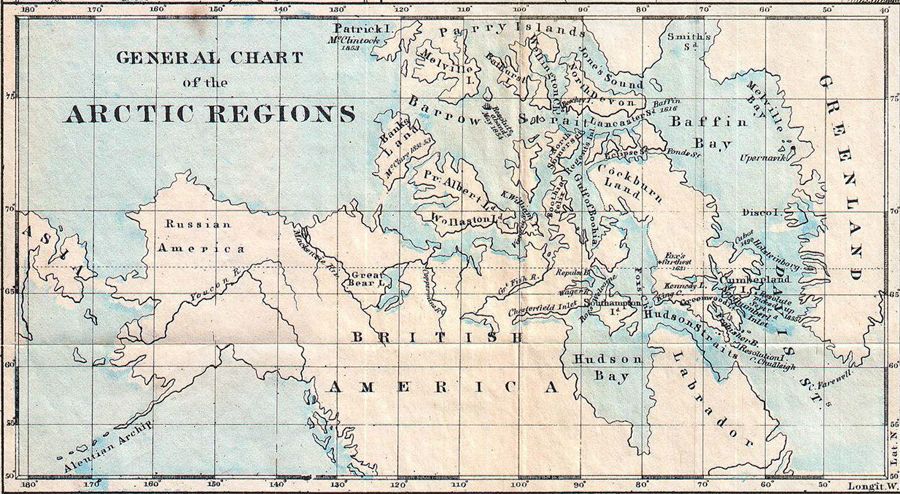

Davis Strait - The Snowdrop's destination

Baffin Island - home of the Snowdrop's Inuit friends

Cape Haven - Inuit settlement and trading station

Countess of Warwick Sound - the Snowdrop's wreck site

Grinnell Glacier - Ritchie crosses with Inuit

Saddleback Island - Inuit settlement

Hudson Strait - Ritchie's goal for a passing rescue ship

Newfoundland to St John's - the rescued crew is reunited

"A Chart of Frobisher Bay", CF Hall, 1865 via Wikimedia Commons

The Snowdrop: Lost in the Arctic

Author: Paul Brown

Agent: Richard Pike

Rights info: IPPicks.com

Published April 11, 2024.

This is a work of non-fiction. Everything between quotation marks comes from written and verbal accounts of the events described.

With thanks to: Andy Barnett at The Maggie Law Maritime Museum in Gourdon, Scotland; Scout Noffke and Morgan Swan at the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire; Robert Ritchie; and Thomas Ritchie.

Paul Brown is the author of The Rocketbelt Caper and The Ruhleben Football Association. His latest book is The Tyne Bridge.

For bonus content, including more details from the Snowdrop story plus unused artwork, visit singulardiscoveries.com.

More from Paul Brown

The Dog and the Dinosaur

The epic true story of a war hero, his rescued dog, and their improbable quest to find a living brontosaurus in the Congo.

Sins Dyed In Blood

The untold true story of Edward Robinson, the lost pirate who sailed with Blackbeard during the Golden Age of Piracy.

The Female Horse Thief

How did a lovestruck English heiress become a notorious American criminal? And why has history erased her identity?

Death of an Angel

The police said it was an accident. The Guardian Angels accused them of racially-motivated murder. Who shot Frank Melvin?

Singular Discoveries

Newsletter and podcast focusing on unusual and extraordinary true stories from forgotten corners of the past.